Having started a re-reading of Perez’ Wonder Woman reboot, in light of Heinberg’s current one, I was struck with just how many distinctive creative revisions are taken to Diana’s story that, in some form or another, highlight her status as a political heroine. Moreover, whether intentionally or not, the changes made by Perez also provided a means by which Diana’s status as a feminist could become definitively measured. In the past William Moulton Marston has been credited for defining Diana as a feminist heroine, whether implicitly or explicitly, and through a reading back it is interesting to attempt an understanding of the particular brand of feminism he was espousing. In his reboot, Perez makes moves that redefine Diana’s feminism to fit into a specific context. What follows is an attempt at being brief on some of the key factors involved in that process, as well as some of the other notable developments that seem to evidence a liberalising of Wonder Woman as a heroine.

Having started a re-reading of Perez’ Wonder Woman reboot, in light of Heinberg’s current one, I was struck with just how many distinctive creative revisions are taken to Diana’s story that, in some form or another, highlight her status as a political heroine. Moreover, whether intentionally or not, the changes made by Perez also provided a means by which Diana’s status as a feminist could become definitively measured. In the past William Moulton Marston has been credited for defining Diana as a feminist heroine, whether implicitly or explicitly, and through a reading back it is interesting to attempt an understanding of the particular brand of feminism he was espousing. In his reboot, Perez makes moves that redefine Diana’s feminism to fit into a specific context. What follows is an attempt at being brief on some of the key factors involved in that process, as well as some of the other notable developments that seem to evidence a liberalising of Wonder Woman as a heroine.1) The Loss of Romance

Whether you loved it or you hated it, Perez decision to take what had been Diana’s primary love interest for so many years and age him so significantly as to be off limits is a poignant one. Steve Trevor and Diana’s love for him, which, in the original story had been a key factor in Diana’s quest to Man’s World, now becomes slightly less influential. While his relationship with Diana remains important, it is the absence of its sexual and romantic nature that is most intriguing. In this simple move, Perez importantly allows Diana to define herself, her motivations becoming more than simply for the intrigue and love of another. While I am not sure if I agree with the removal of romance from her story overall, the impression it leaves, the seeming attempt to identify Diana from the outset as having her own story, rather than tying her immedietely to a love interest, is interesting to me. In this move, Perez also removes the default heterosexual status of Diana as a heroine. That is not to say that he makes her a lesbian or revises her sexuality in any way, but rather that he leaves her sexuality open by refusing to introduce her with an immediate love interest. Though he later introduces Superman as a potential crush for Diana, the encounter serves more to highlight Diana’s naiveté, and her reverence for the Gods than a sexual identity. And despite romantic attention from Hermes, Diana remains solo for the duration of Perez’ run. While this has been the source of much consternation for many, it is intriguing to see how this step has managed to present an image of Diana as relatable to all sexualities, because she has no specific one according to which one must strive. In the fantasy of identifying with Diana, her sexuality, at least, is not an obstacle in Perez’ run, but is a eutral plateau apon which projection becomes possible. Also significantly, Perez continued to introduce a variety of all-ages, all-sexualities cast members, setting the stage for Diana’s to be a tale of openness and liberality.

2) The defining of Patriarchy

In the very first issue, Perez weaves the tale of the rape of the Amazons as the crescendo of their conflict with the patriarchal regime. It becomes central to the way in which the Amazons come to regard the outside world, and is therefore an important aspect in the consciousness of Diana as she grows. The intellectual and spiritual, as well as the martial prowess, of the Amazons is emphasised to portray women with strong and intricate philosophies, and to illustrate those characteristics that suffer under the repressive structures of a patriarchal regime. Here it feels as if Perez is creating the tone and feel of the feminism of his cast, though its boundaries have yet to be set. He is concerned with the outcomes of sexual violence, and does not shy away from its horror. By doing so Perez allows for the possibility of aligning the concerns and beliefs of the Amazons to real-world feminist issues rather than allowing for their message or concerns to devolve into the symbolic or generic. He takes a very real, very present danger, and by showing them as at risk of that danger he does, at least to me, succeed in creating an aspect of the Amazons that makes them relatable, and makes a discussion of politics possible within the text.

3) The Costume

By detaching the link between Diana’s costume and the American flag that can be seen in its pattern, Perez makes another step towards individualizing Diana, and also highlights the disjuncture between her own culture and the one she comes to protect. While in her inception, Diana’s relationship with America and the War effort was distinctly patriotic (as were many of the roles played in her secret identity), in his reboot Perez breaks her ties to America as representative of it as a nation. While it becomes her home, her links to its political and philosophical structure are no longer there, rendering her again, rightly or wrongly, a more open and flexible heroine. It subsequently becomes possible for one to draw comparisons between a whole range of international ideologies and the causes Diana represents, allowing for but not limiting to America alone.

4) The Ambassador

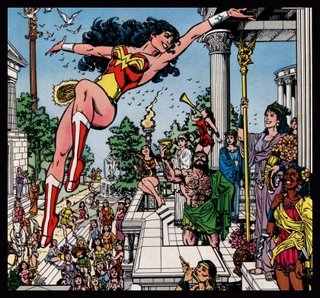

After her initial mission in Man’s World, Diana’s motivation for staying there is immediately one of ambassador and teacher, as a representative of her culture, on her mother’s request. As such Perez sends Diana straight into a political rather than simply heroic role. Diana becomes the site for politics, a conversation about cultural differences. Again, a comparison to Marston’s original setup seems appropriate. The philosophies of Marston’s own Wonder Woman, particularly his own brand of feminism and its ties to some tenets of BDSM philosophy, are not to be underestimated. What is notable is that these differences were portrayed far more in terms of gender, not cultural differences. While they were presented as aspects of Amazon culture, they were universalised as female characteristics, thereby making the essential division one between man and woman. In lieu of the times however, Perez’ own political conversation takes place on a variety of fronts, with cultural differences being the basis upon which more conflict and contradiction is then discussed.

5) Defining his Feminism

During an important and rather epic story arc, Perez introduces the Bana Mighdall Amazons, a splinter group of Amazons existing in Man’s World for some time, yet separate from them. They are ruthless mercenaries, long corrupted by war, running their city as arms dealers. Despite having developed in Man’s World, their relationship to men is more antagonistic (in light of their own personal history), and based on conflict, need, supply and demand. Their radical nature provides an interesting contrast to their Themysciran counterparts, helping to draw a line around the kind of feminism Perez is seeking to define for them. Unfortunately, and as a result, his construction of the Bana Mighdall Amazons might be read as some alternative brand of feminism, and possibly belies some of Perez own views about the roads to which radicalism and separatism lead. It is an unfortunate side effect, in that if the dichotomy between the Themyscirans and the Bana Mighdall Amazons is to be read in terms of feminisms, then whichever the latter represents is bound to suffer a poor rep as a result due to their negative portrayal, while the Themyscirans become the ‘good feminists’ by default. The extent to which their relationship is supposed to be read in this way is obviously beyond me to definitively say, but it raises some important issues concerning the extent to which Perez may or may not have been trying to set up a particular feminism for Diana. If it is indeed the case, then it is important for highlighting the possibility of feminisms as a plural, rather than the generic straw-man ‘Feminism’ that could have been the case. Perhaps it would had been more satisfying to have a more truly representative presentation of the possibilities, but an attempt is a move nonetheless.

(It is important to note here, that this is not the only time it is possible to read the presentation of the Bana Amazons as a bad metaphor for radical feminism; the introduction of Artemis years later is a horrible example of the constructing of straw-man radical feminism seemingly used in order to undermine it as unsound, something that has thankfully not detracted from Artemis’ subsequent success as a character. Whether or not this can be blamed on Perez initial design for the Banas, is something I’ve yet to explore.)

Phew! well, those are the more central themes that strike me at present, i am sure more will arise as i re-read. As ever, i enquire, any thoughts?