The name ‘Wonder Boy’ is one suspiciously absent from the current comic book world. Wonder Woman has never had a young male sidekick, and in light of the families of her respective DC trinity associates, that fact is curious in its conspicuousness. For both Batman and Superman, there is a recognisably distinct family of characters, from both sides of the gender spectrum, sharing panel time, and often their own titles, with their patrons.

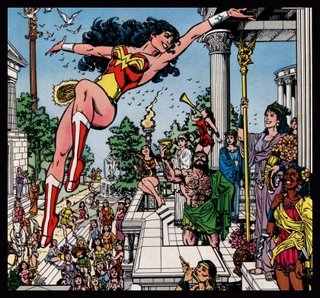

Wonder Woman’s family, by contrast, has primarily been a female-only space. Along with the two Wonder Girls, fellow Wonder Women Hippolyta and Artemis, as well as Nubia, have been touted at times as members of the Wonder Family. Attempts to incorporate men into the adventuring cast of the Wonder Woman title are often hampered by their status as love interests. So, why no Wonder Boy?

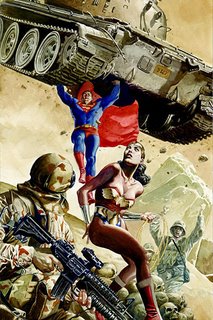

Is it because of gender discomfort? By this I am referring to the gender connotations that having a young male hero inspired by a female icon like Wonder Woman might generate. In the current masculinist culture of comics in general, it is easy to see how a Wonder Boy character would be picked on for being the male sidekick of a female superhero. Yet all around the DCU, young women have and are taking up arms in the name of their male icons. Supergirl, Batgirl, Miss Martian, Speedy, Aquagirl…all of them have been at times accepted as legitimate heroines without questions to their femininity. Clearly we are comfortable with female interpretations of what were started as male traditions (though not in all cases, as Stephanie as Robin stands to prove), yet I am not sure the same would be the case for a Wonder Boy.

The recent introduction of a Power Boy is one of the only examples I can think of where a Heroine’s title has been taken and applied to a male, yet even there the urgency with which he has been disassociated from Power Girl as a namesake, and also turned into an obsessive and abusive ‘himbo’ is a worrying example for how seriously male interpretations of female traditions might be taken in the DCU. And the fact that Karen is herself a take on the Supergirl character as derived from Superman would pretty much undermine Power Boy as an example anyway. Which leaves us with…not very much.

The problem here isn’t that a Wonder Boy would be necessarily effeminate because he had a female namesake, but because it’s imaginable people would joke about it anyway, both within the text and outside it. I can just see the whispering during his first outing with the Teen Titans, or the questions about whether he’d wear a tiara too…And moreover, I wouldn’t place the line at being a questioning of his masculinity, but also his sexuality. I daresay a Wonder Boy wouldn’t just be the focus for joke about femininity, but for homosexuality as well. The way in which we live in a culture that still predominantly views gender and sexuality as collapsible categories makes it inevitable that expectations about femininity will become linked to the desire for men as a love-object, and vice versa. If Wonder Boy were questioned about his masculinity, questions about his sexuality would go hand in hand. It’s infuriating, but I daresay an annoying truth. Moreover, Wonder Woman’s status as something of a ‘gay icon’, while seemingly free from affecting her female co-stars, is something that I would hazard a guess would come to affect the attitudes towards a Wonder Boy.

Here’s the rub for me: what would be the problem if Wonder Boy were effeminate? And moreover, what if he was gay as well as effeminate. Would that be a big problem?

In an article I was reading the other day to which this post owes its title, Eve Sedgwick looks at how the image of the young effeminate male has become the spectre of the adult gay rights movement. Consistently in gay and pro-gay literature, there is a cultural emphasis and value placed on the gay male who isn’t feminine, who is masculine and takes part in a typically ‘masculine’ ontology. This move is important because it seeks to debunk the supposed link between sexuality and gender by maintaining that it is possible to be masculine and still desire men. The downside in that move, and the placing of value on this breaking of stereotypes is that the effeminate gay man becomes marginal within an already marginalized group. In psychological literature, where homosexuality has been removed from the DSM as an example of mental disorder, Sedgwick notes how there is still an apparent need to identify young male femininity as ‘Gender Disorder’. While various aspects of society have been able to move forward with regards to an open view of sexualities, the transgression of gender lines still seems to evoke discomfort, and returns to speak about what is ‘natural’.

Taking it back to Wonder Boy, if we were to introduce a Wonder Boy who is masculine and heterosexual, we would do a good job of debunking the presumed link between gender and sexuality, but we would also perpetuate the value judgement that relegates femininity in males to being an example of disorder. Because it is such a predictable outcome that a Wonder Boy would be a prime subject for questions about his sexuality and his masculinity, any attempts to contradict a stereotype would have the adverse affect of reinforcing the stereotype as something we fear.

Generally, whether or not a Wonder Boy is a big manly man or not, and whether or not he desires men, women, both or none, isn’t something that would usually concern me. However, since Jimenez introduced the character of Bobby Barnes into the Wonder Woman mythos, a character who was then not only ignored from any future issues but also met a great deal of fan scorn, I’ve been left mulling over the concept of a ‘Wonder Boy’ for some time.

For those who weren’t around for issue 188 of Jimenez’ run on Wonder Woman, Bobby Barnes was introduced as the nephew of Diana’s then love-interest Trevor, and was a young African American boy who idolised Wonder Woman and was blown away to finally meet her, receive an honorary ‘Wonder Boy’ t-shirt, and be invited to Themyscira where he could be seen sharing his panel position with Cassie as Wonder Girl. The potential for taking this optimistic young boy further in the Wonder Woman mythos and actually making him a real Wonder Boy was hampered by the fact that his uncle was killed off in the very next story-arc after Jimenez’ departure. Yet the potential for conflict between Bobby and Diana over Trevor’s death seems like a curious dropping of the ball as far as creating an interesting Wonder Boy character. Bobby could easily have returned as a newly empowered Wonder Boy to take issue with his uncle’s death, or perhaps to honour it by fighting by Diana’s side.

In any case, Bobby was forgotten from his one-issue appearance, though not without some conflict on the DC message boards. The issue of Bobby’s debut was also Jimenez’ final issue, and was a tribute to Lynda Carter. Jimenez has always been open about being a young gay man inspired by Carter’s on-screen superheroics, and how important watching the show had been for him. As a result, the strong reactions against his work, and this issue in particular, were often hard to distinguish from the general homophobia he could often receive on the message boards. Fans picked on the issue for being action-lite, and for Diana’s radical amount of costume changes throughout. It was pretty, optimistic, and some might say a little thin on content, but in the spirit of the show it honoured, it was a fun issue. Nevertheless, the readers came out in force to chastise Jimenez for fulfilling his childhood fantasies on the page at best, and promoting some kind of ‘gay aesthetic’ at worst. Attacks on the content of the issue were a thin veil for some of the homophobic abuse levelled at Bobby as a projection of Jimenez within the text, and gave a good indication for the kinds of controversy I feel writing a potentially gay Wonder Boy could arouse. The example of Jimenez’ introduction of Bobby provides another problem with the investments of a Wonder Boy; the idea that the character might become a vehicle for the politics of his creator, or will be accused as such.

As with the issues discussed earlier concerning Wonder Boy’s masculinity and sexuality, there is an almost inevitably political component to introducing a young man into the Wonder Woman mythos, one that would be difficult to avoid for any writer at the helm. If Wonder Woman is till to be considered a feminist symbol or icon, does that apply to her protégé’s, and would that include a Wonder Boy? If the double-w has become a symbol of Amazonian heritage and courage, can a man wear it and what are the connotations if so? Does DC have the current creativity and subtlety to explore those issues without resorting to stereotype; to introduce a male character with a female mentor and primary companions, without resorting to stereotypical tropes? Would the avoidance of stereotype simple reinforce them anyway? The questions I have raised above, along with the rest of this discussion, are just examples of the kind that could take place. Yet despite the hotbed of connotation, I am even more inspired that a Wonder Boy is something the Wonder Woman mythos needs, possibly because of the symbolic implications his absence currently represents.

Any thoughts?