Prompted by a discussion on this blog, I decided to take a second look the other night at The Sandman: A Game Of You, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman instalment dealing with issues of gender and identity.

Towards the end of the tale a drag queen** called Wanda is killed as her apartment building falls during a storm while she is looking after the sleeping form of her friend Barbie. Barbie attends her funeral, where a family friend is keen to impress the idea that Wanda is to be remembered as ‘Alvin’, not Wanda; ‘his’ ‘true’* identity. ‘His’ family never approved of ‘his’ transgendered behaviour, and as a result honours the memory they see fit.

They do so by carving the name ‘Alvin’ into her/his headstone, an act of defiance against the Wanda identity. In retaliation, and once the ceremony is over, Barbie writes the name ‘Wanda’ in lipstick over the headstone, though we know the likelihood of it remaining there is small.

In the discussion that inspired this post, Alabaster insightfully points out how this opposition between Alvin and Wanda fits into the ‘private vs public pain’ idea I discuss earlier in this blog(not sure how to link to the discussion, scroll down to my 'public vs private pain' post and call up the comments). Alvin is the public persona, the male, the socially acceptable character, whose loss is something the family mourn. The woman ‘he’ had become, Wanda, is seen as a contravention of that image. Wanda is the woman Alvin’s family did not lose, because they never accepted her in the first place. The suffering of Wanda is not something to be grieved for, it is the private pain that will never be known to those in attendance at the funeral, they will only remember the Alvin that was publicly known before.

At the same time however, there are other dichotomies set up by the Alvin in stone/Wanda in lipstick idea that bear some commentary.

By inscribing the name ‘Alvin’ on the headstone, it appears concrete, natural, certain, while the transience of ‘Wanda’, written in lipstick, suggests fragility, instability, uncertainty, and also its status as a construction. But the metaphor runs perhaps more deeply than that. Gaiman seems to make a fine choice by using a headstone. Though it suggests its permanence, it undermines it as well. For what is a headstone before it is a headstone? Veritably, it is a blank tablet, tabula rasa, upon which we inscribe the messages of how we

want to be remembered. The inscription on the stone is an act of defiance and also illusion. It is an attempt to make ‘Alvin’ a certainty, to create the illusion of his naturalness. But its still just an attempt, it’s a construction, it is an attempt to carve some kind of truth into a form that was, initially, a blank canvas. While the family want Alvin to be true, they do so with an act that inherently undermines their endeavour, by highlighting the way we attempt to inscribe permanence onto identity that is inherently fluid and undefined.

The choice of the lipstick, inevitably transient (we all understand how often it can need to be reapplied, Barbie does so to her lips in the space of just a few pages), used to write the name 'Wanda', is also a sort of social commentary on identity. Simply understood, as I saw it, it might seem to be a message saying that our attempts to change ourselves, our identities, despite their symbolic importance, is futile, that it must take place against a ‘natural’ form, such as the headstone suggests. But again the metaphor might run more deeply. Perhaps it is a commentary on the way that we suggest some forms of knowledge as legitimate, and others as unreliable. ‘Alvin’ as set in stone appears natural because it is a majority thought, it is the normative state of affairs, it is our reverence for the scientific and the biological. ‘Wanda’ in lipstick is the way that we often make bold statements against science, against notions of the ‘natural’, but how ultimately we live in a society that allows for a framework which undermines those statements, where the questioning of biology with the way we feel, or the questioning of science with a personal narrative, is seen as a poor way of phrasing the question, is an illegitimate claim. Gaiman is, quite possibly, passing comment on how we allow certain discourses the status of privilege while we let others seem questionable, when all of them are in fact as contingent as each other. Science and biology have been constructed to seem impenetrable, but they too share contingent foundations, they too are constructed discourses. While the lipstick could indeed wash away in the rain, a powerful enough sanding device would erase that ‘Alvin’ inscription from the headstone, and with the right tools carving another wouldn’t be too difficult. Whether we should be endeavouring for new inscriptions however, new ways of trying to enforce the legitimacy of our claims, I’m not sure.

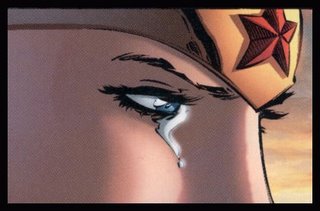

Finally, and quite beautifully, we have an image of Wanda after death, now appearing as a ‘complete’ female, the image of femininity as Wanda had sought out, ‘like Glinda in the Oz movie’. Her perfection, the fact that she doesn’t look ‘artificial’ is commented on by Barbie, who dreams of her. Initially to me, that image seemed bleak, the suggestion being that only in death could we achieve the realisation of identity as we want it to be. The idea that the self-defining of gender was impossible in this life; that only in death would we ever be able to transcend biological gender (i.e. never). But I think that’s not the idea that Gaiman’s text should evoke, nor is it the one i think Gaiman actually cues us for. As has been mentioned, I think, throughout the Sandman run, Death is not a state of permanence, oblivion or end, but a metaphor for a

change of state, from one thing to another. Perhaps, with his final image of Wanda, Gaiman is suggesting that change is in the making of it, that in order to have the identities we want, we must work towards a change of the state of affairs we have now. We must move to a point where personal narratives are just as important as the scientific biological ones; where we do not seek to make certain forms of knowledge as the legitimate ones, but render them all equal to one another. If we push for real changes of state (or State?) we enable the changes in ourselves.

I think that image is a far more optimistic one than I initially gave the text credit for presenting, and one I would much rather allow Gaiman the privilege of being responsible for, and Alabaster for prompting me to look for.

alex x

*I put these terms in quotations to problematise their supposed certainty. Wanda is described as Alvin, and as a ‘he’ even though it contravenes Wanda’s self-description, which is the one I would personally want to lend more credence to out of respect. I problematise the term ‘true’ to undermine its objectivity.

** Initially, my description of Wanda was as a transvestite. I was then promptly reminded by someone, Kate (to whom I'm grateful) how important it is to get terminology right when describing transgendered characters, and was informed (with second opinion also) that transvestite might not be the best term. I went back to the text, and on a second look, found that the official blurb on the back of my edition describes Wanda as a drag queen, while the introduction describes her as a 'would-be transsexual'. I am going with drag queen, if only to be true to the text, and because the 'would-be' prefix to transsexual just doesn't sit too well with me.