So then I read Wonder Woman 226, and the satisfaction and inspiration I found in the previous issue took a bit of a down turn.

There are many ways I could, if I wanted to, spin this issue to a positive end. In its pages, the relationship between Diana and Kal, Wonder Woman and Superman, is explored through a series of poignant vignettes, depicting key scenes in their lives and in their relationship. The lean is definitely towards Diana, the stories within are mostly specific to important happenings within her own narrative, and Superman’s part in being her friend during those times.

In a strange way, this issue should appeal to some of my most emotive academic and personal interests. Metaphorically at least, the story explodes the idea of the individual as a singular entity, by constantly referring back to the way we, as individuals, and Diana, as an Ambassador/Heroine/Woman, are defined by the people we let into our lives, those other individuals who share our experiences. No matter how we try to draw lines between ourselves and the other people in our lives, we find ourselves irrevocably involved in them, and them in us. We experience joy, sorrow, love, but we do so with other people there to share them, inspire them, nurture them, be our focus. This issue demonstrates that quite beautifully, showing Diana in some of her happiest and tragic moments, and the way Kal has been there in one way or another to give them audience, an ear, a shoulder, a smile.

Another academic interest in this issue comes from the metaphor it provides concerning the binary opposition of man/woman. By interweaving the lives of Diana and Kal, or perhaps more Kal into Diana’s, the issue serves as an example of man and woman as categories which define, reify and yet also undermine one another. Indeed, there are many ways this issue explodes and problematises the dichotomies of man/woman, inside/outside, that the likes of Eve Sedgwick and Ed Cohen have done such good work discussing academically, though I won’t go into them here.

Yet, in all of this, I still can’t seem to move past some of the wider implications of the issue. This was to serve as the final issue of Wonder Woman. Not the ending (as purposefully explained in the previous issue) but an ending at least. Yet for some reason, the possibilities that fact implied for the subject matter were abandoned in favour of an instalment in the wider storyline of Infinite Crisis playing out across the DCU.

The choice to review the relationship between Superman and Wonder Woman seems to gain its impetus from the fact that their friendship had recently suffered much difficulty within the text. While the most striking part of that conflict (their fight in issue 219) did indeed occur within the pages of Wonder Woman, the drama of their crumbled relationship actually occurred elsewhere; in the preceding chapters of the Sacrifice arc (where Diana and Kal first came to blows and also odds), and in the pages of Infinite Crisis itself. What’s more, while issue 226’ review served as a kind of prompt to all those of us who were either unaware of or had forgotten about the importance of that relationship, the resolution of their conflict also occurred in the pages of Infinite Crisis, rather than in Diana’s title itself.

As such the issue suggests for me a sense of unfulfillment, an instalment in a wider narrative (a metanarrative perhaps?) that, while having an important effect on Diana’s story, was not, in fact, her story. This is not a story of ‘Wonder Woman’, but rather about something else, and seems to have missed the opportunity to bear any relationship to the very first issue for a sense of closure, or indeed any particular thematic points from previous issues. It practically ignores the supporting cast of recent years, as well as any of the other threads left over from Rucka’s run (such as the Ares/Circe/Lyta situation, Vanessa Kapatelis, Leslie’s relationship with Ferdinand, or her conflict with Veronica Cale etc) and instead attempts a reinterpretation of history. Its strange, for an issue that does in fact recall a series of events from previous Wonder Woman issues, it seems to bear very little resemblance to any of them, or to provide them with much more meaning, the vignettes so overshadowed by the wider implications of the text and its relationship to Infinite Crisis.

Much worse, the continuity is wrong. I am in one mind about the two implications of that particular problem. On the one hand, if these continuity glitches were a mistake, they evidence an editorial laziness not quite acceptable for the final issue of any title, let alone one of DC’s flagship characters. Secondly, if these glitches were in fact deliberate revisions, part of DC’s attempt to establish a new continuity to its ‘New Earth’ in the wake of Infinite Crisis, then this is simply more fuel to the already raging fire that this issue was not the final issue of Wonder Woman, but a chapter in a different story altogether, and speaks ill sentiment of editorial appreciation for Diana as a character.

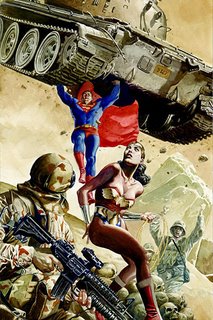

What provides this issue with such a disappointing resonance was the way it fails to capitalise on the promise of the previous issue. As discussed in the first part of this thread, the previous issue was all about moving away from grand narratives down to personal ones, it was about changing the world heart by heart, it was about renewed faith in Diana’s story, her uniqueness, her personal touch. This issue, rather than providing us with a continuation of that theme, relegates the continuation of Diana’s story to only one or two pages at the end, using the rest of the issue to tie her up to Superman. Another disappointing aspect to that choice is that Superman is such a larger than life character, bringing with him so much of his own mythology, that his presence within the text doesn’t exactly overshadow Diana, but threatens to suggest that her story can only take place in the context of his own. For much of her comic book career since the 1940s, people have fallen back on describing the character of Wonder Woman as ‘Superman lite’, his star-spangled female counterpart, rather than acknowledging the idiosyncratic points that make her such a unique heroine. By choosing to have her share panel time with Superman in what was to be her final issue, the result is a reinstating of that old assumption, a kind of step back from trying to set Diana with a unique place in the DCU. Even the cover to the issue, shown above, represents Diana in a diminutive position with regards to Superman, his shadow and presence gaining their overpowering context from her rather demure physical pose. The context of Infinite Crisis also accentuates the idea that Diana's personal narrative is being disregarded in favour of another narrative, even within her own book.

And so, from going forward so brightly in the previous issue, where the importance of Diana’s personal narrative seemed so clear, this issue does a hell of a good job reminding us that Diana’s story is one that is subject to the whims of higher powers and wider happenings. It is the comic book version of a TV ‘clip show’, and had it been entered somewhere else, i.e. as a chapter in an annual, a special, or some other collection of stories, or indeed even as an earlier issue, it might have been a good clip show. But in the context of being the final issue? It is a whimper rather than the bang Rucka’s run had consistently proven itself to be, and I suspect more of a testament to bad editorial decision-making than his writing. Still, I couldn’t help but feel short changed, and would be very interested to hear Rucka’s thoughts on the matter.

And yours.

alex x