Way back in my piece on the prospect of introducing a Wonder Boy into the ‘Wonder’ family, I touched upon a reading by Eve Sedgwick entitled ‘How to Bring Your Children Up Gay’, an ironic title whose article examined, among other things, the way in which effeminacy in gay males is decried at its most simplistic as a sign of abnormality by the more conservatively inclined, and at its more complex, a perpetuation of stereotype that can, and is often, rejected by even adult gay men. The criticism of ‘nancy boy’ or ‘sissy’ is not simply the supposed dominion of the heterosexual bigot; it is employed just as vindictively among gay men as an attack on the legitimacy of more ‘effeminate’ gay men. And why? For many, the criticism is an honourable one; to be a gay ‘sissy boy’ supposedly undermines the queer challenge to heteronormative assumptions that gender and sexuality are inevitably linked. If the simplistic and inefficacious assumption is that a gay man is simply a female in a man’s body, then the gay man who behaves according to a broad understanding of what it is to be ‘feminine’ perpetuates the legitimacy of the assumption, rather than challenging the binaries upholding the claim. The value judgment you’ll find as an extension of this, that ‘straight acting’ or ‘masculine’ gay men are the ‘ideal’, is, as far as I’m concerned, just as insidiously homophobic as statements like ‘why can’t gay men simply behave normally’, or ‘why can’t they act more like us?’

The result of the rejection of effeminacy, whilst making an interesting statement (for the challenge to an inevitable link between gender and sexuality is indeed an important one), renders marginal the experiences of gay men who do fall into that category, or more broadly the category of ‘stereotype’. Popular culture has us at an awful double bind. Behave according to the stereotypical understanding of what it is to be a gay man, and you’ll be presumed ‘understood’ and ‘accepted’ enough to appear on Will and Grace, but you’ll also face the rejection of your politically minded peers desperate to smash that stereotype. Attempt to smash the stereotype, and you get ousted from the mainstream understanding of what it is to be a gay man, and you end up launching a critique on your peers who do seemingly affirm that stereotype.

What exactly does this all have to do with comics? For me, this debate around effeminacy, and more broadly stereotype, dictates the way in which the campaign for fair representation of gay men within comics must proceed, and also sheds light on the frustratingly simplistic ways similar discussions about women as readers of comics have gone forward. As a gay male comic book reader, the need to defend my reading of titles like Wonder Woman or Manhunter becomes inevitably tied to the way we let stereotype inform our value judgements about readers. And also, as a gay male comic book reader, there is an element of personal politics that inevitably shapes my choices, and the representations of other gay men I find acceptable to consume.

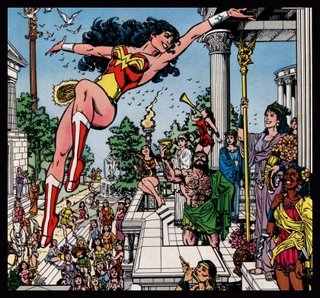

To take things back specifically to my own experience here, the progression of my own political concerns has often shaped not simply the way I have bought and read comics, but the extent to which those practices have been featured in other areas of my life. As a young boy, I was a huge Wonder Woman fan. I never stopped being one; I’ve been following her adventures in some form or other since I was 5. Looking at the rest of my comic book collection as a child, I see the entire Jessica Drew as Spider-Woman run, complete with appearances in other titles. I see Firestar, Batgirl, and a fair amount of the Black Cat. And yet the extent to which that reading played a part in my friendships or school-life is marginal; reading female-headed comics as a kid would have been understood by peers and family as a marker indicative of a sexuality I was keen not to disclose. As I got older my readings shifted, I became more affluent, and also more dedicated, branching out to the majority of the DCU and some Vertigo titles. But looking at the ones that frame the majority of my collection…The Teen Titans, Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Birds of Prey, Checkmate, Sandman, Promethea, Manhunter, Lucifer, Y The Last Man…all comics featuring, if not starring, strong and diverse portrayals of female characters. As time went on, the admission of my comic book preferences, as well as the heroines I watched on TV (Buffy, Xena, Alias) went hand-in-hand with the disclosure of my sexual identity. The link between them, if not truly one made by me, was one I internalised enough to treat them with equal delicacy. For me here, what seems to become an interesting relationship to examine is the growth and development of my sexual identity and its effect, if any, on the comics I have consumed, and why. Is there any reason one can ledge an assumption that a gay male comic book reader would gravitate towards particular portrayals of strong females in comics? And what part do I play in a contribution to the success of that assumption?

In short, here’s the thing, the concern, the issue that prompts this entry. Do I like these comics because I am a gay man; are they an extension of some sort of gay aesthetic, one linked similarly to notions of effeminacy? The stereotype of the tiara-wearing gay comic fan, with his Lynda Carter obsession, is rife in the comic spheres, and to all appearances (albeit sans any tiaras and only moderate interest in Lynda Carter), that stereotype finds an example in me. Throughout the years, and only up until I was 19 or so, my interest in comics, and Wonder Woman specifically, has been downplayed in other areas of my life. In recent years however, I own more Wonder Woman t-shirts than I do Superman comics, I’m looking to shape my Masters around my interest in comics, my friends buy me comic-related memorabilia, heck my friends in New Zealand refer to me as Wonder Boy. Comfortable as I am with my interests and aesthetics, stereotypical or not, I am more keen than ever to examine the way in which we read meaning into our comic reading as indicative of who we are.

I am keen to undermine the idea that I read the comics I do simply because I self-identify as gay. Rather, the comics I read now more than ever before have become inevitably entwined with my political concerns. Heavily influenced by the online feminist community here, I have become incredibly concerned with finding empowering, strong, diverse, rich portrayals of women in comics. Not because I want to prove they exist, but because this is where I identify the enjoyment in my reading. To attempt to read that back, to look at causes and effects, to establish a link between my sexuality and my comic-book preferences, only works I feel because my politics act as the link between them both. From my sexuality extends the fundamental concern of my politics; diversity. Based on that, my academic readings dictate my appreciation of postmodernism and the poststructural undermining of identity (from which I read Y the Last Man, or the Sandman for instance). It is on those bases that I delight in non-normative portrayals of all types of individuals in comics, most especially women, because the transgressive possibility of diversity in their representation is so provocative.

I know that some of that may seem almost unnecessarily complex, but I would maintain that only such a level of complexity is ever fruitful when we come to discuss the relationship between the identities we uphold and the way we consume comics. It is a lack of this complexity that often undermines the discussion of women as readers, as creators and as characters in comics in more mainstream circles. The call to compile lists of ‘girl-friendly’ comics, to understand what it is ‘women’ want to read in comics, what should be aimed at them, how they should appear within comics, is forever apparent, forever reinforced, forever debated. And in the further reaches of the blogosphere, the call for similar discussion in relation to homosexual readers and characters also celebrates debate. I fear, at least as we currently understand it, these debates to be based in largely unhelpful terms.

To try to isolate what it is that makes a woman, or a gay comic book reader, is a hopelessly obtuse endeavour. To further obtain some kind of general understanding of what ‘they’ want to see is equally insensitive. But to look at political concerns, as much of the feminist blogosphere is doing, helps to move discussions away from hopeless ‘what makes women tick’ discussions to anecdotal looks at various different women’s experiences as readers of comics, and how their private interpretations of their genders and politics inform the way they consume comics.

As my own reading goes on, and my writings in this blog develop, my exploration of the links between my understanding of my sexuality, my politics, and my comic book preferences will be something I will hope to consistently emphasise. And I would appeal, from a private curiosity, and also a devotion to diversity, that others might do similarly. As ever the comment section of this blog is open for contribution and comment for people to share their interpretations.

And so, any thoughts?

Alex x

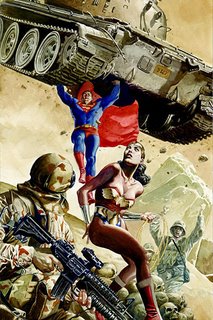

Ok. I’m going to start what may promise to be a bit of a long entry with a moment of internet silence, while we all gulp back those initial gut reactions to seeing yet another blog thread with ‘Kara’ in the title. Yes, this shall be another discussion of the current Kara Zor El, otherwise known as Supergirl, and yes, I gather that we (the comic-blog-reading folk among us) are probably quite sick of these by now. And no, I can’t promise you originality. All I can do is give you my honesty on a subject that has bugged me since the revamp, and continued to as its been argued so heatedly about it across the net. (For those of you wanting to read up on what’s gone before, hop on over to ‘When Fangirls Attack’, you’ll find more than your pleasure.)

Ok. I’m going to start what may promise to be a bit of a long entry with a moment of internet silence, while we all gulp back those initial gut reactions to seeing yet another blog thread with ‘Kara’ in the title. Yes, this shall be another discussion of the current Kara Zor El, otherwise known as Supergirl, and yes, I gather that we (the comic-blog-reading folk among us) are probably quite sick of these by now. And no, I can’t promise you originality. All I can do is give you my honesty on a subject that has bugged me since the revamp, and continued to as its been argued so heatedly about it across the net. (For those of you wanting to read up on what’s gone before, hop on over to ‘When Fangirls Attack’, you’ll find more than your pleasure.)